One name that I keep encountering during these fairy tale posts is that of 16th/17th century Italian courtier, poet and lyricist Giambattista Basile. Most of Basile’s work was never translated into English, and has fallen into obscurity even in his native country, with one exception: his posthumous fairy tale collection Lo cunto de li cunti overo lo trattenemiento de peccerille (The Story of Stories, or Entertainment for Little Ones) better known to us today as Il Pentamerone.

The five volumes contain early versions of several European fairy tales, with a Cinderella who murders one of her two stepmothers (this is great), a Rapunzel who summons a wolf to gobble up the ogre who has imprisoned her (this is also great), a Sleeping Beauty who fails to wake up from a kiss and is instead raped in her sleep (this is less great), along with irritated observations about court life in southern Italy (Basile was not a fan), humanity (Basile was also not a fan) and anyone not lucky enough to be Italian, and more specifically, from the Neapolitan region (Basile was seriously not a fan). Brutal, vicious, often racist, and filled with terrible puns, they are not the versions most familiar to us today, in part because many writers and editors who encountered the tales seem to have had the same reaction: I so need to rewrite these.

Basile’s early life was lived in obscurity, so obscure that we are not sure of his father’s name or his birthdate. He was probably born, however, in 1575 in a small village just outside Naples. His parents may have been prosperous farmers—Basile’s later work shows a strong familiarity with farm life—or perhaps skilled artisans. Whatever their origins, his parents seem to have been wealthy enough to find placements at court for Basile and at least some of his siblings, as well as musical training, although it is also possible that they obtained these positions through merit and talent, not money.

Three of those siblings became professional musicians. For whatever reason, Basile was initially less successful at court, and ended up meandering around Italy, finally arriving in Venice. Here, his court connections and skills were enough to obtain a short lived military career and a membership in a Venetian literary society, which may be where he encountered the writings of Dante, Plutarch, and Boccaccio, major influences on his literary work. Eventually, however, either he tired of Venice or Venice tired of him, and he returned to Naples.

Once home, he found himself welcomed to at least the outer fringes of high society, and began to write his first books and publishing poems, songs, and plays, most written in literary Italian. On the strength of these works, in 1611 he joined the new Accademia degli Oziosi, joining aristocratic poets like Giovanni Battista Manso (who would later be the recipient of a fulsome yet boring poem written in his honor by John Milton) and other scholars and writers.

Literary work, however, failed to pay the bills, and in between publishing books and musical works, Basile found himself taking up a number of estate management and paperwork positions for various nobles. The experience left him with a decided distaste for court life. As he noted in Il Pentamerone:

Oh, hapless is he who is condemned to live in that hell that goes by the name of court, where flattery is sold by the basket, malice and bad services measured by the quintal, and deceit and betrayal weighed by the bushel!

This is one of his kinder comments. The courts of his tales are corrupt, precarious places even when its members aren’t engaged in rape, incest, adultery, murder, defecation, torture and cannibalism (come to court for the food, stay for the human flesh.) Kings, queens, princes, princesses, courtiers and servants find themselves rising and falling, wealthy and happy one minute and crawling through sewers the next, in an echo of the vicissitudes of fortune Basile himself had witnessed or experienced as he bounced from one noble employer to the next.

By 1624, however, Basile had resigned himself enough to court life to start calling himself the “Count of Torone,” and to continue to take on various estate management positions until he died of the flu in 1631. His sister arranged for his unpublished work to be published in various installments. Among those works: Lo cunto de li cunti, published in five separate volumes under a pen name Basile had used before, Gian Alesio Abbatutis. As an anagram of his name, the pseudonym did nothing to conceal his identity, but it was useful for distinguishing between his writings in literary Italian and his writings in the Neapolitan vernacular.

Lo cunto de li cunti, or, as it was later called, Il Pentamerone, was at least partly inspired by the earlier 1353 work of Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron. A collection of exactly 100 stories supposedly recited by ten wealthy aristocrats fleeing the Black Death, The Decameron was both immensely popular and deeply influential throughout Europe, inspiring others, such as Geoffrey Chaucer, to write their own collections of tales. From Basile’s point of view, The Decameron had another major significance: along with the work of Dante and Petrarch, it helped establish vernacular Italian—specifically, the Tuscan dialect spoken in the area around Florence—as an intellectual language equal to Latin.

Basile wanted to do the same for the Neapolitan dialect, establishing that the vernacular of Naples could also be used as a literary and intellectual language. This would help open up literacy, education and religion to those unfamiliar with literary Italian and Latin, still the dominant intellectual languages of the Italian peninsula, allowing others to enjoy the same social mobility that he and his siblings had experienced. A literary Neapolitan dialect could also help preserve the local culture and possibly help serve as a bulwark against further political and cultural colonization from Spain, northern Africa, and Turkey—a major concern for an Italian kingdom all too familiar with invasions, eyeing the aspirations of Spanish monarchs with dread.

Thus, Basile wrote Il Pentamerone not in literary Italian—a language he spoke and wrote fluently—but in the Neapolitan dialect, a choice that later added to the comparative obscurity of his versions until the tales were translated into Italian. He also followed the basic structure of The Decameron, using a framing story to collect the tales, and having his storytellers tell exactly ten stories per day—though in what may have been meant as a self-deprecating gesture, or as a nod to the greatness of his predecessor, Basile told only fifty tales instead of one hundred. And, like The Decameron, his stories, for the most part, were not original, but nearly all contain some ethical or political point, often spelled out in the narrative, or framed in a pithy proverb or saying.

The collections also have several sharp differences. The Decameron is set against a real event: the arrival of the Black Death to Italy. Basile, in contrast, sets his storytellers within a fairy tale of their own. Boccaccio’s storytellers were all elegant men and women with lovely names; Basile’s storytellers are fearsome elderly ladies. Boccaccio’s stories often serve as an escape, at least for their narrators, from reality; Basile’s fairy tale characters often find themselves facing grim realities. Boccaccio explicitly wrote for an adult audience; Basile claimed that his stories were simply entertainment for little ones.

I say “claimed” here for several reasons. Basile was certainly not the only early fairy tale writer to claim to be writing for children—indeed, two later French salon writers who drew from his works, Charles Perrault and Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont, made exactly the same claim. But their versions are generally appropriate for most children. Basile’s tales are not, even before we get to the cannibalism. His own framing story acknowledges this: the storytellers and listeners are all adults. “Entertainment for little ones” thus seems less of an accurate description and more of a sarcastic or self-deprecating comment—or perhaps an acknowledgement that many of Basile’s tales may have been based on oral stories told to children. Or perhaps he was referring to the morals, proverbs and observations about life added to nearly every tale—a touch that Perrault and de Beaumont would later copy. It’s unclear.

As an attempt to establish the Neapolitan dialect as a major literary and intellectual language, Il Pentamerone was a failure. The Italian that eventually became the main language of the peninsula, popularized through books, radio, film and—eventually—television was based on the literary language established by Dante and Boccaccio—that is, the Tuscan dialect of more northern areas, and Basile’s works in Neapolitan slowly fell into obscurity into his own country since they could not be read.

But as an inspiration for later fairy tale writers, Il Pentamerone was an enormous success. If most readers could not access the original Neapolitan, they could access the later translations into Italian and other languages. Once translated, the tales from Il Pentamerone slowly found their way into other collections, edited, altered or transformed. Charles Perrault, for instance, dove into Il Pentamerone to find “Sleeping Beauty,” “Puss in Boots,” and a few details for his version of “Cinderella,” and elements from Il Pentamerone appear in many other French salon fairy tales. Faced with their own concerns about foreign influences, the Grimm brothers, linguistics by inclination, and deeply impressed by both an Italian translation of Il Pentamerone and Basile’s original linguistic goals, decided to follow Basile’s example and collect their own fairy tales as a representation of their culture. Andrew Lang couldn’t quite bring himself to include some of Basile’s more brutal texts into his fairy tale collections, but he did include one or two highly edited versions based on an edited, expurgated translation by John Edward Taylor—itself based on an edited, expurgated Italian translation that left quite a few of the more vulgar parts out, introducing Basile’s tales to English readers.

In a few cases, however, Basile’s stories made it into collections moderately unscathed. I was delighted to see, for instance, that the original version of the story of Peruonto was not too far off from the version I first read in a children’s book of Italian fairy tales. Granted, the kid’s version left out all of the insults, the midwife, the references to the Roman Empire, and a couple of racist comments, and also discreetly moved the birth of the twins to a time after marriage—but the protagonist’s ongoing demands for raisins and figs remained, as did the plot of the tale, and to be fair, at the age of seven, I would not have been that interested in references to the Roman Empire. Another story in my children’s book actually received an extra paragraph explaining the tense political situation in medieval Sicily to explain some of the comments in the tale.

The versions currently available for free on the internet are not from my children’s book, but rather from an edited 19th century translation by John Edward Taylor now in the public domain, which preserve the basic plots and violence, but not all the verbiage. Interested readers should be aware that Basile’s full text contains several racist elements, starting with its framing tale, as well as multiple misogynistic and casually anti-Semitic statements, many of which also remain in the Taylor translation. Some of Basile’s misogyny, granted, seems to mostly serve as a reflection of the attitudes of his contemporaries, as in sentences like this:

All of the pleasure of the past tales was muddied by the miserable story of those poor lovers, and for a good while everyone looked like a baby girl had just been born.

In some cases, Basile even uses character’s internalized misogyny against them, as in the tale of a woman who adamantly refuses to believe that the crossdresser in front of her is a woman, not a man—on the basis that no woman could shoot a gun or control a large horse so well. The assumption is completely wrong. Basile also occasionally argues that woman should have a certain autonomy, as well as some choice in their marriage partners. These moments somewhat mitigate the misogyny, but not the virulent racism or the anti-Semitism, prominent in the unexpurgated translations.

But for all of their brutality, sex and racism—perhaps because of their brutality, sex, and racism—Basile’s tales managed to maintain a powerful hold on those readers who could find them. It says something that as a small child, I reread Peruonto over and over again, even in its severely edited version, laughing at the eponymous character’s near obsession with figs and raisins, delighted at the moment where the king admits his mistake. It says still more, perhaps, that when Charles Perrault was searching for fairy tales to tell to children, he turned not to the intricate, subversive stories of his fellow fairy tale writers in French salons, but to these boisterous, vulgar tales filled with people who never hesitated to betray and eat one another. (Excepting Peruonto, who just wanted figs and raisins.) His characters may be horrible people, but their stories remain compelling.

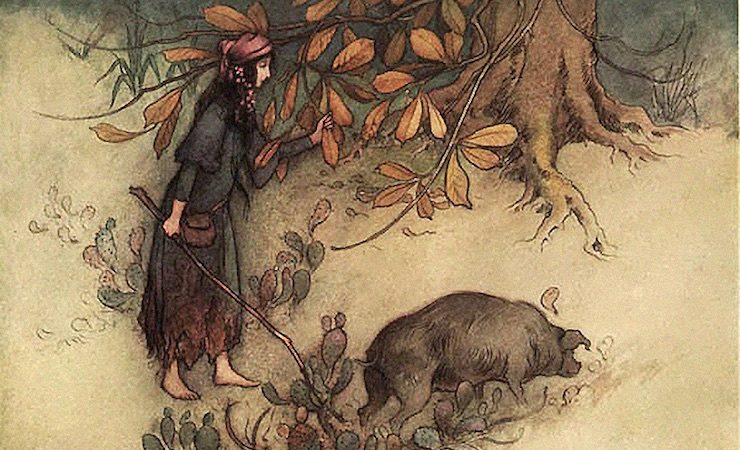

Top image: Illustration by Warwick Goble for “The Golden Root”, from Stories from the Pentamerone. Macmillan & Co., 1911.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.